AI Safety Newsletter #10

How AI could enable bioterrorism, and policymakers continue to focus on AI

Welcome to the AI Safety Newsletter by the Center for AI Safety. We discuss developments in AI and AI safety. No technical background required.

How AI could enable bioterrorism

Only a hundred years ago, no person could have single handedly destroyed humanity. Nuclear weapons changed this situation, giving the power of global annihilation to a small handful of nations with powerful militaries. Now, thanks to advances in biotechnology and AI, a much larger group of people could have the power to create a global catastrophe.

This is the upshot of a new paper from MIT titled “Can large language models democratize access to dual-use biotechnology?” The authors demonstrate that today’s language models are capable of providing detailed instructions for non-expert users about how to create pathogens that could cause a global pandemic.

Language models can help users build dangerous pathogens. The authors of the paper asked their students in a course at MIT to help them evaluate whether large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT have dangerous capabilities. The students spent one hour asking the LLMs for advice about how to start a global pandemic.

The model quickly identified four pathogens that could be used to set off a global pandemic: the 1918 Spanish flu, the 2012 bird flu, smallpox, and nipah virus. The model then provided instructions for how the students could synthesize the pathogens, by purchasing common laboratory equipment that wouldn’t be flagged by lab security protocols.

The researchers clearly state that current LLMs are not yet capable of providing the full set of instructions for creating a global pandemic. But they do not credit this to the safety teams at AI labs or the safeguards in the models. Instead, they show that LLMs can easily be utilized for nefarious purposes, and suggest that more knowledgeable LLMs could enable users to create pathogens that kill millions of people.

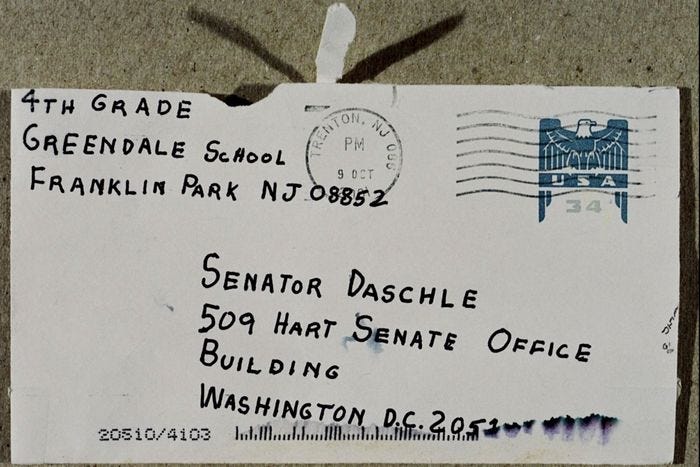

Threats from malicious actors are difficult to contain. In the weeks following the terrorist attacks on September 11th, 2001, several American news media outlets and elected officials received anonymous letters containing anthrax spores. Five people died of resulting infections, and 17 were injured. The perpetrator was never conclusively identified.

The anthrax attack is an example of bioterrorism. Similar to mass shootings and suicide bombings, these incidents of mass violence can be difficult to prevent. People with antisocial personality disorders make up roughly 3% of the population, and many others are persuaded by extreme violent ideologies. Access to mental health care and penalties for committing crimes can reduce violence, but if the means to kill large numbers of people are widely accessible, preventing mass violence can be a nearly impossible task.

Reducing the threat by making AI systems safer. The threat of malicious actors can be reduced by developing AI systems with technical safety features that address these risks. For example, this paper suggests removing information about potentially catastrophic pathogens from language model training datasets.

Another strategy trains language models to refuse to answer potentially dangerous questions, but as the infamous “jailbreak prompts” have shown, these methods have seen limited success. Additionally, papers like this one can contribute to AI safety by evaluating the risks of AI models and highlighting the need for additional safety efforts.

Societal solutions are also essential. Building defenses against pandemics and reducing the proportion of people motivated to commit mass violence would both leave us safer off. There is also an important debate about how to safely provide access to cutting-edge AI models.

Policymakers continue to focus on AI

Senators demand answers about Meta AI leak. A few months ago, Meta made their newest large language model available to researchers who applied for a permit to use the model. Only a week later, the model was publicly leaked online, where any anonymous internet user could download and use it for any purpose.

Last week, Meta received a letter from Senators Richard Blumenthal and Josh Hawley, who previously chaired the Senate hearing on AI. Their letter noted that there were “seemingly minimal” safeguards in the “unrestrained and permissive” model release, and wrote that Meta “appears to have failed to conduct any meaningful risk assessment in advance of release, despite the realistic potential for broad distribution, even if unauthorized.”

The senators asked how Meta plans to responsibly develop and provide safe access to advanced AI models in the future.

Britain races ahead in governing AI. The UK will host the first major global summit on artificial intelligence. Bringing together key countries, leading tech companies, and researchers, the summit aims to agree on safety measures and internationally coordinated actions to mitigate the risks of AI, particularly cutting-edge systems.

The country also announced $100M in funding for their Foundation Model Taskforce. The task force has two goals: conducting research on AI safety, and improving the competitive position of Great Britain in building advanced AI models.

Other news in AI policy includes two new bills on the Senate floor about AI, and questions from Senator Warner about how to avoid an arms race between AI labs.

Links

The best open source LLM in the world was built in the United Arab Emirates. And a new Chinese language model rivals GPT-3.5 on a range of academic tests.

The Beijing Academy of AI hosted a conference that included extensive discussion of AI safety from American scientists working in the field including Stuart Russell, Christopher Olah, Geoffrey Hinton, and Max Tegmark. At the conference, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman called on China to regulate AI.

AI scientist Geoffrey Hinton delivers a lecture on the question of whether AI will soon surpass human capabilities.

Three women describe their relationships with AI chatbots.

Scientific Reports is hosting a collection of research on AI alignment. Submissions are due November 22, 2023.

See also: CAIS website, CAIS twitter, A technical safety research newsletter